A little while ago, I wrote an article explaining what a style sheet was, mainly for my own clients, so I could send them a link when I sent their completed work and style sheet to them.

A little while ago, I wrote an article explaining what a style sheet was, mainly for my own clients, so I could send them a link when I sent their completed work and style sheet to them.

It struck me, though, that it might be useful to write about style sheets from the perspective of the editor / proofreader as well (I’m going to use “editor” to refer to both here, for simplicity, unless I’m distinguishing between the two).

I assume this will primarily be useful for people new to editing who are picking up tips from those of us who have been in the game a little longer. But whoever you are and however long you’ve been editing, do pop a comment below if you have anything to contribute!

What is a style sheet?

A style sheet is a list which spells out how things are to be done when writing and/or editing a text, including information on spellings, hyphenation and capitalisation, referencing and special information. Its aim is to keep texts consistent.

When you’re an editor, you will encounter three types of style sheet:

- Style sheets you receive from someone earlier in the process or general ones prepared by particular publishers, journals, etc.

- Style sheets you create yourself as you work on a project

- Style sheets created by the previous editor when you’re taking over a job or doing the proofreading for something that’s previously been edited (this is unfortunately rare, in my experience)

All three types serve the same purpose: to record the style decisions (more on this later) that have been made in order to keep the look, feel and detail of the text or texts consistent.

When you’re creating a style sheet, it might only be for a single use, for a single client (e.g. a PhD student). When one is created by a journal or publisher, it’s usually so that their “house style” will be consistent across publications and journal issues. But the idea is the same: it’s a tool that’s used to keep things consistent.

What do you mean by “style decisions”?

English is a funny old language. Even if you’re adhering strictly to one of the major style guides, (Chicago Manual of Style, Oxford Style, etc.), you will find there is still room for choice in some aspect of your text.

An example where even Oxford didn’t tell me what to do: I was editing a set of articles which included lots and lots of words and phrases in a different language to English. Each then had the English translation in some form before or after the foreign word. Of course, the articles were all written by different people who had used different ways to express this (word in italics / non-italics / double or single quotation marks and English in parentheses or not, italics or not, quotation marks or not). I was looking to make this consistent … but after some rules on what to do, Oxford told me to choose a way I did this as long as it was consistent!

There will also often be individual names, phrases, etc. in the text you’re editing which will need to be set out in a consistent way, which might not have rules.

An example where there can’t be any rules: your client has lots of interviewees and they’ve referred to them with a code to ensure anonymity. Do they put Respondent OH1, just OH1, OH-1, (OH1), [OH1], etc., etc.?

Although a client a while ago said that his first editor “kept it all in his head”, I prefer to note all of this down so I have it to refer to and keep things consistent.

What does a style sheet look like?

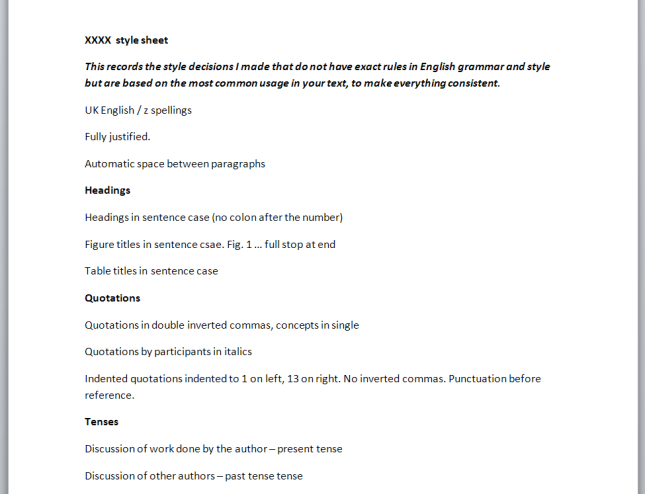

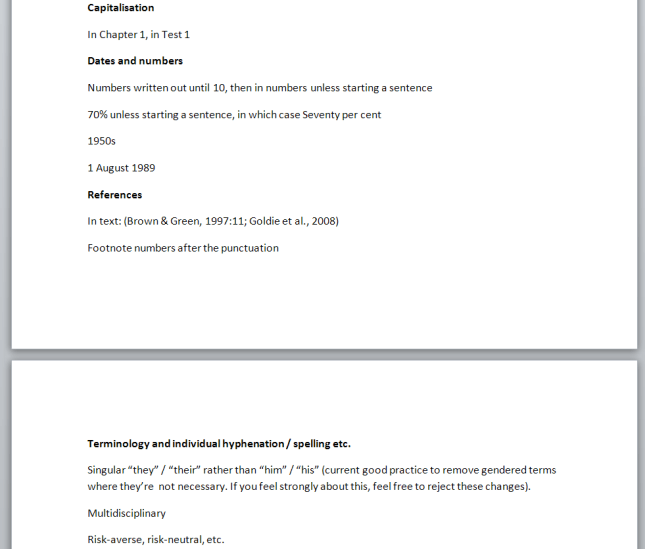

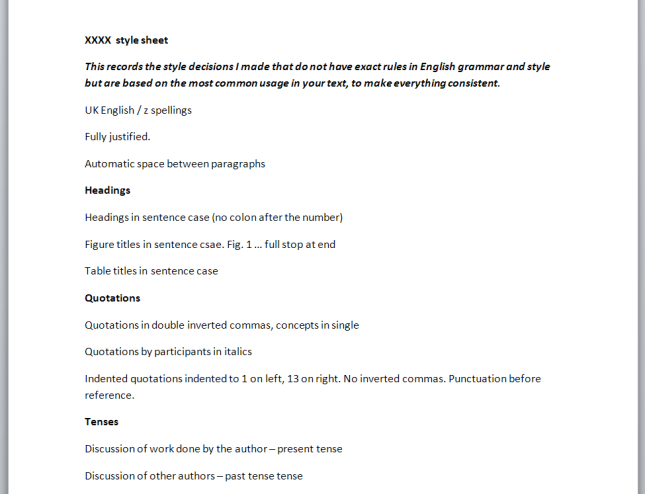

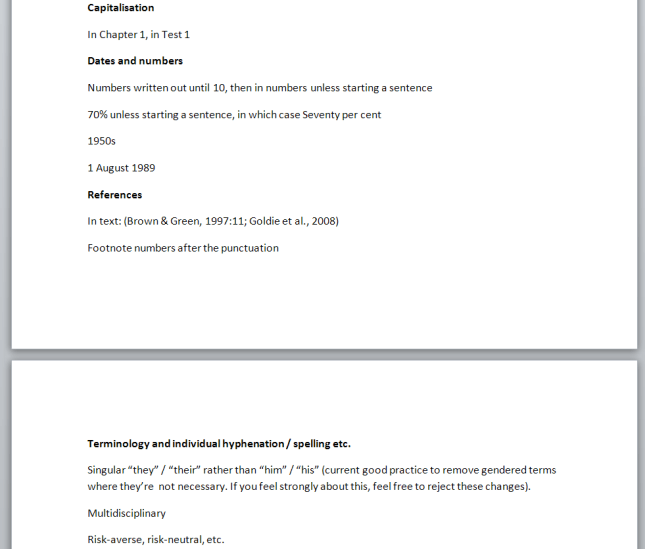

I’m sharing here an example of one of my own style sheets. Note that I have a little explanatory note at the top to explain what it is.

You can see that I set out the most common things that can differ (in my experience) and need noting down – s or z spellings, how the paragraphs are set out, how the headings and figure / table titles are set out, etc.

In the second half, I go on to dates and numbers, how references are laid out, and some specific things to do with the particular text I’m working on.

I find that a publisher’s style sheet is set out in the same way, although it might sometimes be online or a pdf with links.

If I’m working on a text destined for a particular publisher or journal article, if their own style sheet is very long and my text is quite simple and doesn’t need all that detail, I’ll often summarise the parts I need on my sheet anyway.

When should I set up a style sheet?

I set up one of these for any text that …

- Isn’t for a publisher or journal that has its own style sheet

- Is for a publisher or journal that has its own style sheet but that sheet is very long and complex and I can use a summary

- Is more than a few pages long

- Is being sent to me chapter by chapter (this happens with PhDs I work on)

- Is going to form part of a larger body of work or a series (e.g. the regular publications of an organisation

- Is being worked on with a colleague – this is quite rare but does happen

When and why should I send a style sheet to my client?

I pretty well always send the style sheet to my client along with my completed work.

I typically send it with a note in the email directing the client to my explanatory article, as I’ve found that most of my clients haven’t come across this before (I happen to work with a lot of students and self-publishers, as well as translation agencies; your experience may differ if you mainly work with publishers).

I will send the style sheet to my client if …

- They’ve asked me a lot of questions about grammar and wording issues before we start (I will probably pop down the standard hyphenation and capitalisation rules on it if that’s the case)

- They are likely to add to the text (for example if I’ve pointed out gaps or missing references)

- They are sending me their work chapter by chapter – sending the style sheet with the first chapter can often nip certain issues in the bud, the client learns from it and they’ll be more consistent in the next chapter (I’m always so happy when this happens!)

- They plan to send me regular publications, etc. – if they didn’t have a style sheet I provide one for their writers to use, making my work easier and less time-consuming and meaning they have less to correct

- It’s a substantial document (more than a few pages)

Hopefully, having a style sheet from me will mean that the client will keep things more consistent in the future.

I do also mention that they should send this on to their proofreader if they’re planning to use one in the next stage of publication. This saves their proofreader from busily changing all the Chapter Ones to chapter 1 (or at least it explains that it was an active, considered choice on my part, and not an error).

Making changes to a style sheet

If I send my style sheet to my client mid-way through a project, for example with their first PhD chapter, I ask them to look through it carefully and let me know if there’s anything they’d like to change or they’re not happy with. Sometimes in this case I ask them questions (e.g. “You’ve used ‘Interviewee RD1’ and ‘RD1’ in equal numbers in your text; which one would you prefer to use throughout it?”). If they give me feedback, I record that, or if they ask to change something and their change does actually defy a stated grammar rule I will explain why I can’t.

Working with an established style sheet

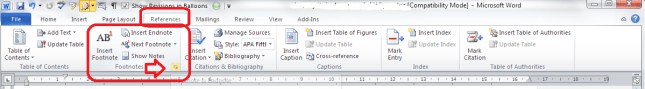

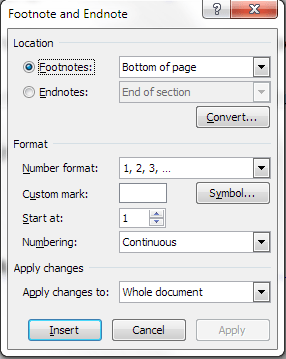

If the text I’m working on is destined for a publisher or journal that has a full style sheet, I will of course obey that to the letter, to make things as easy as possible for the in-house editor or designer. Even if that means leaving footnote numbers before the punctuation, something I don’t like to do (but some publishers prefer).

If I’m proofreading a text that someone else has already edited, or I’m working on for example corrections in a PhD that someone else has worked on, I will use their style sheet to guide the changes I make. Even if I don’t approve of their decisions personally, as long as they don’t defy a rule of grammar, I’ll keep it consistent (even if I have to move a footnote number to before the punctuation!). I aim to make as few changes as I can at the proofreading stage, in order to keep corrections (and the chance of new mistakes creeping in) to a minimum.

—-

I hope this post has been helpful and given you some more information about why we use style sheets, where they come from, setting up your own one and working with your style sheet with your clients. Do pop a comment at the bottom or like and share this article if you’ve found it useful and interesting!

Related posts on this blog

What is a style sheet? For people working with editors